Introduction: The Device’s Cognitive Blind Spot

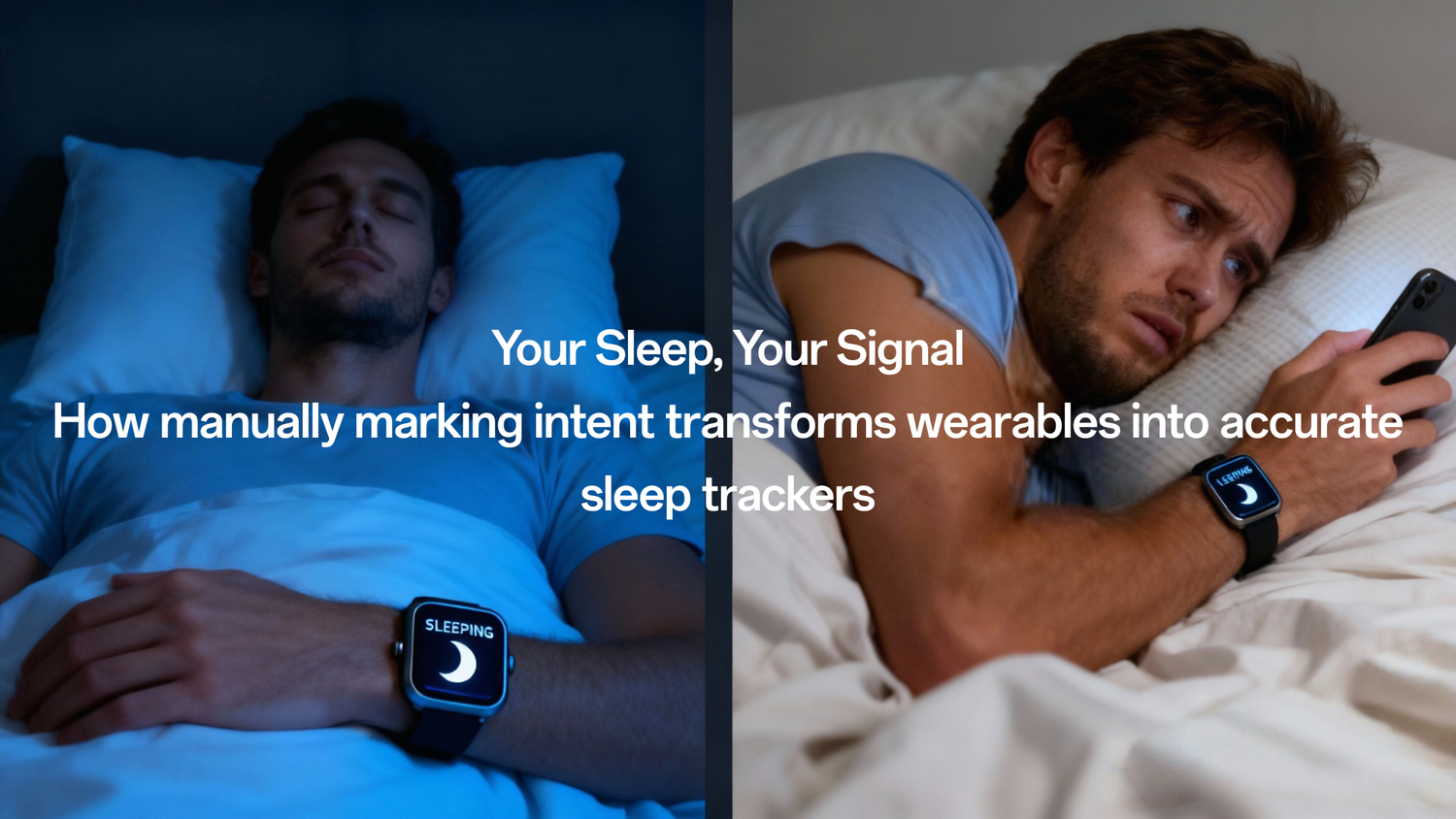

If you own a health tracker, you have lived this contradiction: You lie in bed, scrolling through your phone, fully awake—yet your wearable registers that your sleep has begun. This common experience reveals the core structural flaw in consumer sleep monitoring: the Intention Trap.

Wearable devices (CHTs) are unparalleled in providing continuous, large-scale physiological data. They measure movement via accelerometers and cardiac changes via photoplethysmography (PPG). However, the machine’s most profound failure is its inability to capture the user's intent to sleep (Time Attempting to Sleep, TATS). Since the true determinant of data accuracy is the human input of intent, not the device’s algorithmic judgment, the data we rely on—like how fast we fall asleep—are fundamentally compromised.

This article establishes that the consumer’s greatest misconception about sleep technology is believing the machine can automatically know their intent. To secure the future of objective sleep health, we must embrace the Subjective–Objective Alliance, where the user actively provides the contextual anchors that the sensors cannot sense.

Chapter I: The Illusion of the Boundary

Core Conflict: The technical challenge is not sensor quality; it is the algorithm’s inevitable mistake of equating motionless wakefulness with genuine sleep. This confusion at the onset boundary leads to pervasive, systematic data bias.

1.1 TIB vs. The Sleep Period

In clinical laboratory settings, the start of sleep is anchored to the "lights off" timing. But in real life, the time a person goes to bed (Time In Bed, TIB) and the time they intend to sleep (TATS Start Time) often diverge, particularly due to the increasing use of electronic devices in bed.

- TIB is Subjective: TIB is defined as a subjectively reported behavioral indicator—the time the person chooses to start trying to fall asleep.

- The Sleep Period is Mechanical: What devices actually output is the “Sleep Period” duration. This is mechanically determined by the proprietary algorithm, which identifies the first epoch classified as sleep based primarily on movement reduction.

Since individuals often lie very still while awake, the device’s algorithm, which relies on accelerometry being further reduced in deeper sleep, assumes the individual is already asleep. This is a common failure point for both consumer devices and research-grade actigraphy.

The Scenario: Think of it this way: if you wake up at 3 a.m. and just stare at the ceiling without moving, your device has almost no chance of realizing you’re awake. This phenomenon—the misclassification of motionless wake as sleep—is the root cause of the most significant data error.

1.2 The Price of Misclassification

Because the device struggles to identify resting wakefulness, validation studies comparing wearable output against the Polysomnography (PSG) gold standard show predictable skewing in the data:

- Overestimated Duration: Wearable devices typically tend to overestimate Total Sleep Time (TST). The average bias for TST often indicates devices overestimate sleep, sometimes by over an hour.

- Structural Bias: This bias is structural, manifesting as systematic underestimation of wakefulness. When a clinical population (like those with insomnia) is tested, accuracy is compromised because their sleep is fragmented and contains more WASO.

Why This Matters to You: If your device consistently adds 30 minutes of "quiet time" to your sleep, your reported TST is inflated. This provides a false sense of security, potentially masking real underlying issues. If you struggle with sleep maintenance, your device is likely making your data look better than it truly is, delaying you from seeking clinical advice.

Chapter II: The Consequences of Missing Anchors

Core Conflict: Without the TATS anchor, the objective data points—especially those concerning sleep onset and fragmentation—are rendered unstable, making them unreliable for diagnosis or assessing intervention effectiveness.

2.1 The Crisis of Sleep Latency (SL)

Sleep Onset Latency (SOL)—the time from trying to sleep to actually sleeping—is a primary metric for assessing insomnia. Yet, it is precisely this metric that devices are structurally unable to determine accurately.

- The Missing Link: SL requires combining an objective measure (Sleep Onset, SO) with a subjectively reported time (TATS). Since manufacturers often imply TATS rather than explicitly requiring it, the objective measure is left without its necessary subjective anchor.

- The Verdict: The consensus is clear: No device can provide SOL without a measure of the subjective determination of bedtime. Lacking this, devices tend to underestimate SL, making the user seem to fall asleep faster than they do.

2.2 WASO: The Silent Wake Problem

Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO), the total time spent awake after initially falling asleep, is a critical metric of sleep continuity. However, WASO assessment is considered one of the primary limitations associated with actigraphy-based wearable sleep trackers.

- The WASO Mechanism of Failure: Just as motionless wakefulness at the start of the night is missed, if a person wakes up at 4:00 AM and remains quiet—perhaps lying still or "quietly messaging" on an electronic device—the algorithm cannot distinguish this from light sleep.

- WASO is Underestimated: This means WASO is typically underestimated by consumer-grade devices. This has ripple effects: when WASO is artificially low, Sleep Efficiency (SE) is artificially high, again falsely reassuring the user.

Why This Matters to You: If you are seeking treatment for insomnia, which is often managed in part by objective data, biased SL and WASO estimates are counterproductive. They can undermine treatment efficacy measurements (e.g., in a clinical trial evaluating an intervention). Furthermore, if your SE falls below the 80%–85% threshold, the accuracy of all your sleep measures is likely compromised. Relying only on the device's automatic "Sleep Score"—which is a proprietary measure of unknown operationalization—when your sleep is highly fragmented may lead you to miss the need for clinical intervention.

Chapter III: The Subjective–Objective Alliance

Core Solution: The future of reliable, high-fidelity sleep data is the integration of user input as a standardized sensor. This collaborative model recognizes that the user is the only one who possesses the "ground truth" for the TATS boundary.

3.1 The Mandate for Intent Marking

Authoritative sources, including expert panels from the Sleep Research Society (SRS), consistently recommend that the ambiguity surrounding sleep boundaries must be resolved through manual input.

- Manual Calibration is Essential: Bedtime and wake-up time should only be used when self-reported or manually signaled by the users. This could be through a dedicated event-marker button or through journaling/logging features in the accompanying app.

- Post Hoc Adjustment: For research and clinical use, manual adjustment (post hoc adjusting) of the sleep period boundaries—verifying the start and end times against a subjective sleep diary—is often the preferred choice. This is essential because automated methods to infer the intention to sleep vary widely in performance across devices and are not currently standardized.

- The Limitation of Manual Input: Even manual reports carry caveats, such as potential recall biases and the difficulty of consistently and accurately pressing the marker when extremely sleepy or stressed. Therefore, manual input should be used as a contextual supplement to the objective data, not a replacement for measurement.

3.2 Shifting the Metric Priority: From Single Night to Long-Term Rhythm

Given the inherent volatility and bias in single-night boundary metrics, researchers are pivoting to long-term rhythmicity, where the continuity of data over weeks compensates for night-to-night measurement noise.

- Beyond the Snapshot: While validation studies often rely on single-night PSG comparisons in a laboratory, the intended use of consumer devices is continuous tracking over multiple nights. Multi-night sleep data is crucial for assessing night-to-night variation and revealing habitual sleep patterns.

- Rhythm Metrics as the Anchor: Focus should shift to metrics that track consistency, which are less reliant on precise boundary classification. These include the Interdaily Stability (IS) and the Sleep Regularity Index (SRI). These indicators assess the coherence and timing of rest-activity patterns over a 24-hour period, offering a more stable measure of circadian health.

- The True Objective Measure: The objectively defined Sleep Period duration is preferred over the potentially flawed TIB. This helps separate the truly objective physiology from the user's potentially flawed subjective time construct.

Conclusion: The Path to Personalized Precision

The consumer’s greatest misconception about sleep technology is believing the machine can automatically know the intent to sleep. The core flaw is not technical failure, but a failure of context: the device records data, but only the user can provide meaning.

The solution is the Subjective–Objective Alliance. By accepting the need for user input, we transform the wearable device from a potentially misleading passive recorder into a high-fidelity interactive calibrator. This collaboration allows clinicians and users to leverage the unique capacity of multi-sensor wearables to co-record autonomic parameters and estimate circadian features, advancing the field toward personalized sleep medicine.

Your Actionable Sleep Protocol (The TATS Protocol)

To secure the most accurate, clinically useful data from your wearable:

- 1. Manually Anchor Your Intent (TATS): Do not wait for your device to guess. Manually signal (via app or journaling) the exact moment you start trying to fall asleep and the moment you finalize your wake-up time.

- 2. Trust Trend Over Single Score: Disregard proprietary "Sleep Scores," as their calculation method is often opaque and non-standardized. Focus instead on long-term weekly trends in objective, validated metrics.

- 3. Prioritize Rhythm Metrics: Track Interdaily Stability (IS) or Sleep Regularity Index (SRI). These continuous, multi-night metrics are more robust predictors of overall health than single-night TST or WASO estimates.

- 4. Seek Clinical Advice for Low SE: If your calculated Sleep Efficiency (SE) is consistently lower than 80%–85% (e.g., >3 nights/week over several weeks), seek clinical advice. This persistent low efficiency suggests that the device's accuracy is likely compromised, and a professional assessment is needed.

Laat een reactie achter

Deze site wordt beschermd door hCaptcha en het privacybeleid en de servicevoorwaarden van hCaptcha zijn van toepassing.